Last Updated on July 20, 2020 by John Prendergast

I read this awesome New York Times piece, How Companies Learn Your Secrets, and it got me really interested in peoples habits. Specifically, the science and psychology of how they form and change over time. So I did a little digging, and–surprise!–I learned a few things. Eureka! A new #finsci post is born!

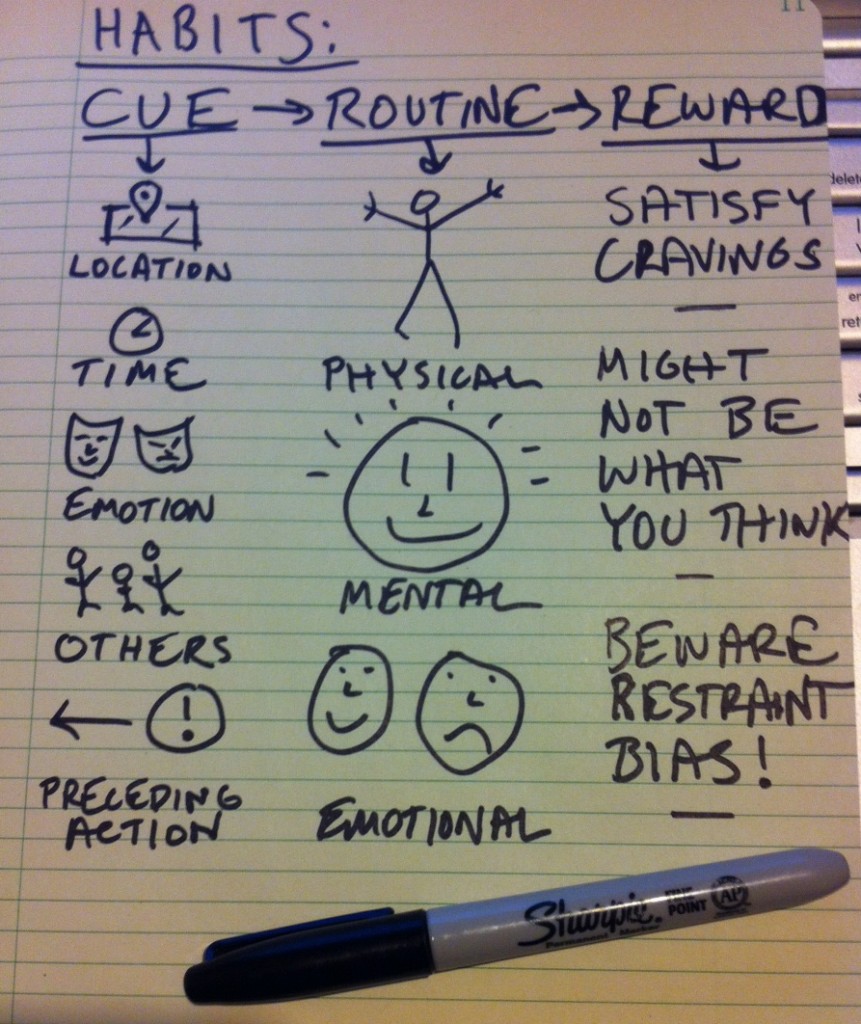

The habit creation process, a three-step loop

- First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use.

- Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional.

- Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.

Over time, this loop — cue, routine, reward; cue, routine, reward — becomes more and more automatic. The cue and reward become neurologically intertwined until a sense of craving emerges.

What’s amazing about cues and rewards, however, is how subtle they can be. Neurological studies like the ones in Graybiel’s lab have revealed that some cues span just milliseconds. And rewards can range from the obvious (like the sugar rush that a morning doughnut habit provides) to the infinitesimal (like the barely noticeable — but measurable — sense of relief the brain experiences after successfully navigating the driveway).

Most cues and rewards, in fact, happen so quickly and are so slight that we are hardly aware of them at all. But these patterns are the main currency of our neural systems which uses them to build automatic behaviors.

(paraphrased from the NYT article mentioned above)

Change is possible

Habits aren’t destiny — they can be ignored, changed or replaced. But it’s also true that once the loop is established and a habit emerges, your brain stops fully participating in decision-making. So unless you deliberately fight a habit, the old pattern will unfold automatically.

So the good news is that if you need to help a client change their savings or spending pattern it’s possible. BUT, as as you already know from your business and personal life, ignoring current habits and creating entirely new ones is difficult. That’s because it takes willpower (possible future #finsci topic) and sustained effort, two scarce resources in human beings.

So how do we make progress ourselves and help our clients do the same? The research in the NYT piece suggests that the most successful strategy to change behavior is to tweak the routine in existing habit loops. In other words, don’t fight the cue and the reward, just insert a new behavior in between.

Think about ex-smokers who quit by devising a way (like chewing on a toothpick) to tweak the routine in response to a que (cravings) and reward that are still there. Now think about the number of those people compared to the number that quit cold turkey. It’s FAR fewer. They tried to use willpower to ignore their que and it turns out our programming, which is the same reinforcement system that motivates us to avoid danger and reproduce, usually overwhelms simple willpower.

Tweaking your habits to be a more productive advisor

Changing Client Habits

Changing your own habits can be really hard. But what about helping clients change their habits? Very very tough. But not impossible. One simple way is help them understand this cycle and suggest an alternative routine.

You can take it even further and help them by using your proactive monitoring tools to set an alert and give feedback when they’re succeeding or struggling. If you don’t have a tool with proactive monitoring and alerting go get one. [Yes, Blueleaf Advisor has this.]

You could also take it further and experiment with some of the new tools coming online that leverage this kind of behavioral economics to encourage the right things. For instance, if you’re trying to encourage savings, you could recommend ImpulseSave (our office mates) to clients.

ImpulseSave turns the act of saving into an impulse that’s as simple as sending a text message. See something you want (cue), use ImpulseSave to put the price of it in savings (new routine), get an email letting you know you’ve just saved money toward your goals (reward). Some of us at Blueleaf use it. It’s fun and it just plain works.

Changing Your Habits

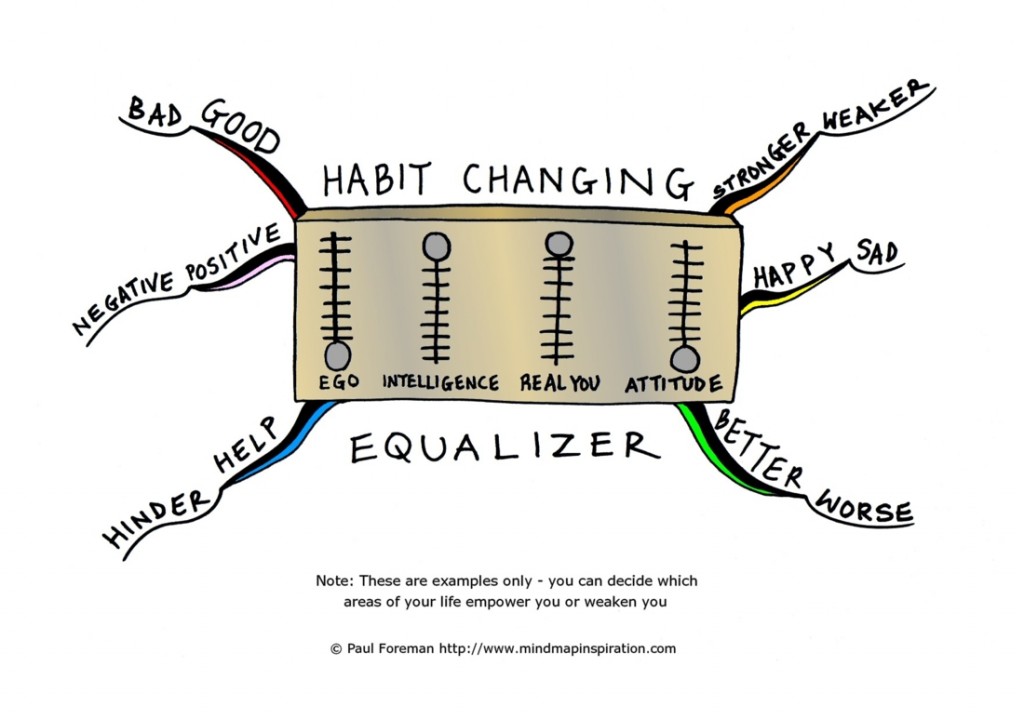

We’ve all got habits we’d like to change. But we’ve got to spend our willpower wisely. Analyzing the habits you want to change — figuring out the cues, routines, and rewards that define them–will help you change them, one at a time.

I think the best way for advisors to use habit science is to tweak their existing habits to increase productivity. If we can identify the cues, routines, and rewards at the heart of procrastination and distraction, then maybe we can solve the “not enough hours in the day” problem. My big productivity killer is:

Twitter.

I periodically, habitually; almost maniacally check my “of interest” list whenever I am at my computer. Let’s say I’ve been working at a Blueleaf blog post for 45 minutes and I reach a brief standstill. I switch to my Twitter tab, refresh the list, and next thing I know I’m 1,000 words deep in an article about parasites found in outdoor cats, which may or may not be making humans go crazy. In a daze, I attempt to return to the writing only to find myself rereading all of my sources and everything I’ve already written just to get the wheels turning and the fingers tapping. Probably lost 20-30 minutes right there. So here’s what I did to tweak my routine:

- Cue: The cue for me is a preceding action. Whenever I reach a brief pause in whatever productive thing I am doing on my computer, I switch to the list and get lost in a sea of links. So the cue is any moment immediately after a spell of productivity.

- Routine: The routine is mental. I switch to the Twitter list, click refresh, and proceed to scan, click, and start reading/watching/listening.

- Reward: The reward, which may be obvious, is distraction. After a spell of productivity, I feel the cue that tells my brain to stop working so hard and enjoy some passive entertainment, a nice mental distraction that makes my brain lazy.

One last thing… On restraint

This bit is from an article called Why We Return To Bad Habits from Scientific American:

If you have ever lost weight on a diet only to gain it all back, you were probably as perplexed as you were disappointed. You felt certain that you had conquered bad eating habits—so what caused the backslide? New research suggests that you may have succumbed to a cognitive distortion called restraint bias. Bolstered by an inflated sense of impulse control, we overexpose ourselves to temptation and fall prey to impulsiveness. When you’ve made progress avoiding your indulgences and that little voice in your head tells you it’s okay to start exposing yourself to temptation again—ignore it.

But don’t ignore us! Subscribe for email updates below: